Przejdź do trybu offline z Player FM !

Chasing Butterflies: Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida – Part 4, Rafael Remy’s Story – Podcast 148

Manage episode 449419055 series 2414495

Previously on Chasing Butterflies – Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida:

After Dolores Carlos’ retirement from acting in South Florida nudie films in the late 1960s, she still remained close to her circle of Cuban filmmaker friends, and none more so than José Prieto, Greg Sandor, and Rafael Remy. They would still meet regularly, and all three took an active interest in her daughter Marcy’s well-being. From time to time, they would joke about the fortune teller that the three men had consulted when they escaped from Cuba. Greg Sandor had moved out the California and had indeed found the money and respect that had been predicted for him. Similarly, José Prieto had found a degree of fame and notoriety following the success and outcry that followed the release of films he made, such as Shanty Tramp (1967) and Savages from Hell (1968). The only exception to the mystic’s forecast was Rafael Remy: he’d fared well and was not seeing the trouble and strife that had been foreseen in his future.

Rafael had lived a lower profile existence but with more regular work than his two friends: due in part to his jack-of-all-trades skill-set and willingness to get involved in anything, he was always in demand. He was a cameraman, editor, lighting, gaffer, soundman, and production manager who was cheap and could always be relied on to deliver a decent job.

But as the 1960s turned into the 70s, the film business was changing: the innocent exploitation films that had greeted them when they arrived from Cuba were giving way to more explicit sex movies whose legality was questionable, and Rafael was suddenly being offered an altogether different kind of job.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many people involved in the Florida film business of the 1960s and 1970s. Their overlapping personal histories reveal an untold chapter of adult film history – and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it. These are some of their stories.

This is the concluding episode of Chasing Butterflies, Part 4: Rafael Remy’s story.

You can listen to the Prologue: Dolores Carlos’ story here, Part 1: Manuel Conde’s story, Part 2: José Prieto’s story, Part 3: Marcy Bichette’s story.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Leroy Griffith, Veronica Acosta, Marcy Bichette, Mikey Bichette, Lousie ‘Bunny’ Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Manny Samaniego, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Herb Jeffries, Tempest Storm, Chester Phebus, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Lynne O’Neill, Something Weird Video, and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 45 minutes long.

*

1. Rafael Remy, the fortune-teller’s prediction – and Emile Harvard

In the late 1960s, Rafael received a called from someone called Emile Allan Harvard.

In a strong Eastern European accent, Harvard explained that he was new to Florida and was looking for a film man: someone who knew how to put a movie together, someone who knew where to find actors, crew, locations, and equipment. Harvard had heard that Rafael could be the man to assist him, and that Rafael was a man with expertise who’d built an extensive network of contacts in the years since he’d arrived penniless from Cuba. But Rafael was wary: he asked around about this new arrival in the state, but could find no one who knew anything about Harvard.

Rafael was right to be cautious: Harvard was a mysterious hustler with an unusual history. Emile Harvard was a Romanian Jew, who’d started his adult life in 1930s Bucharest training to be a cameraman. And then in the build-up to World War 2, Harvard became a spy for the British. It was a volatile period in Romania as the country’s fascist dictatorship was aligned to Nazi Germany and the government was suppressing any opposition by force. Despite the dangers, Harvard loved the subterfuge. He was given a cover profession to conceal his espionage activity which was to be a newsreel cameraman for British Movietone News. He used these media credentials to gain access to key government sites and report on them to his British paymasters. It was a perilous assignment, but one he performed with alacrity.

Romania was a key supplier of the oil for the Nazi war effort and so he also gathered information on the refineries and transport routes. Then he captured footage of Romanian military operations, like airfields and supply depots. But Harvard never seemed happy doing the same activity for long, and soon he was suggesting ways that he could sabotage Nazi efforts. His motivation was less born out of deeply-held ideological convictions, but rather out of a love of excitement and intrigue. A later acquaintance described Harvard as “an enigma, rather than a real person, a shady, shape-shifting person with many identities, a man who you felt you could never truly know.”

The useful life of a spy is a limited one – and in 1943, his cover was blown when Harvard apparently blabbed to someone he shouldn’t have and was reported to the authorities. Life In Romania was suddenly impossible for him so his British employers moved him to Tel Aviv, a city then in British-administered Mandatory Palestine, where he got married and had a daughter, Esther.

When the war ended, Harvard obtained Israeli citizenship before moving to Canada, first Montreal, then Toronto, where he started a career as a TV producer and director. He formed several small-time companies, including Harvard Productions, ostensibly to make television series for the American market. His wartime activity may have been over, but in truth Harvard still enjoyed living a partly fictional life, and with each career move, he inflated the achievements on his resumé which he generously shared with the press. He frequently spoke about working for MGM for twelve years, producing content for NBC, CBS, and Pathé, and having a successful career in Hollywood – none of which was true.

A few years later, without any major credits to his name, Harvard decided on a radical change of direction: after a vacation to see his brother in Miami, Florida in 1960, he was inspired to announce that Harvard Productions was planning a Florida-themed club in Toronto to be called ‘Oceans 11’, after the Rat Pack movie that had hit the cinemas that year. It was to be an exclusive, high-end, rich-members-only place, which he described as a “health and entertainment” club. The Florida theme meant palm trees, a glass sun-roof, a 500-seat restaurant, nightly entertainment, and a swimming pool with a state-of-the-art wave machine – all to be housed on the top three floors of a Toronto office building. “It will be just like Miami Beach,” Harvard told the newspapers, who lapped up the project with excitement filling pages of breathless newsprint. It was ambition on a grand scale, the kind that comes from someone with a big imagination, not to mention someone whose own money is not at stake. Sure enough, the project failed when it was the funding failed to materialize, and so for Emile Harvard and Harvard Productions, it was back to square one.

Just like the wartime spy Harvard had been, the next years were spent donning various different identities and promoting different business schemes. Some seemed serious, others were harebrained. They included hawking time-share properties, selling Jacuzzis, and offering dubious healthcare products (“at last a cure from embarrassing itching!” read the copy for one innovative cream.) Perhaps part of his success came from his appearance: Harvard was a tall, distinguished, and earnest-looking man who projected intelligent seriousness. But in 1967, Harvard was in the news again, this time posing as a doctor, prescribing Belltone hearing aids, and persuading pensioners to sign up for exorbitantly-priced payment plans. He was arrested and charged for his involvement in the fraudulent scheme.

Each time he was embroiled in a scandal, Emile Harvard somehow managed to wriggle out, and re-emerge a year or two later involved in another dodgy deal. The irony was that he was never afraid of the media. Quite the opposite: he was first in line to give newspapers interviews and quotes, just as long as they spelt his name correctly.

*

2. Emile Harvard and ‘Fear of Love’ (1970)

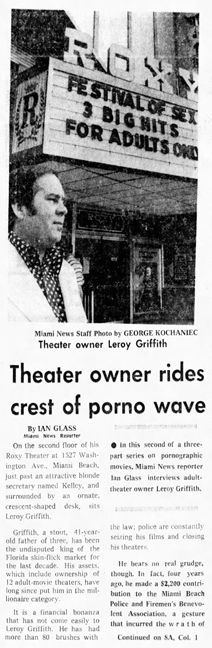

And so, in the late 1960s, on the lam from his latest scam, Harvard turned up in Miami, in his early 50s, with his wife and two teenage children. This time he decided to return to his first love – filmmaking. A cursory glance at the local theater scene in South Florida convinced him that he needed to speak with the most powerful and influential player in town – and that was Leroy Griffith.

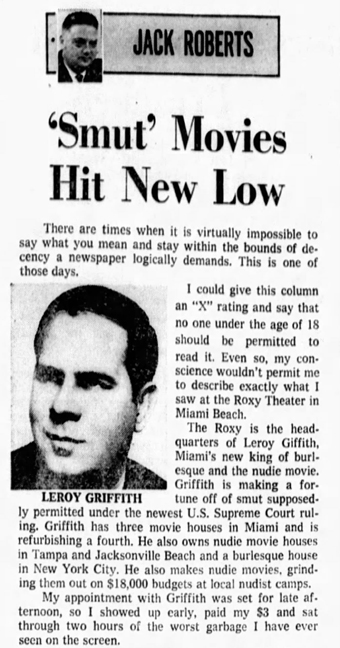

Griffith’s theater business had come a long way since he moved to Miami in the early 1960s and bought the Paris Theater staging burlesque shows with Tempest Storm before meeting Dolores and moving into the sexploitation movie business with men like Manuel Conde. By the early 1970s, Griffith’s empire had grown to 12 adult theaters, including the Paris, Roxy, and Gayety theaters, and 15 adult book stores in the area, and he claimed to have produced 30 softcore adult films too. By now, Griffith was a well-known figure in Miami, though he was at pains to point out, in an interview in 1969, that he made films that specialized in ‘nudity’ and not ‘exploitation.’ ‘Exploitation’, he explained carefully, referred to “torture, fetishes, and lesbianism”, subjects that he just wouldn’t touch.

Griffith was intrigued by Emile Harvard: here was an older, seemingly sophisticated European, who boasted of a successful Hollywood career and wanted to make films for him to exhibit. Griffith told Harvard to speak to José Prieto and Rafael Remy, two men who would give him a crash course download in Florida low-budget filmmaking. So Harvard did, and came away impressed with both the Cubans’ experience. But Harvard explained he wanted to make a different kind of flick. He didn’t want to join the crowded field of slasher films, biker movies, or nudie-cuties: he wanted his films to go further and push the envelope. In short, he wanted to put sex up onscreen. Real sex, sex that happened before your very eyes. Harvard formed a company, set up a small office, and offered José and Rafael in-house jobs working on his upcoming sex film projects.

José was unsure. He didn’t seek film work as much as Rafael, happy to pick up temp jobs outside of the movie business when he needed money and wait for movies that interested him. He also wasn’t sure about making more explicit sex films. They were still illegal, right? He’d had enough of hiding and fleeing from government interest, and now he preferred to keep his head down and enjoy a quiet life. But Rafael felt differently. This could be a new income stream: the films would be cheap, so there would be more of them. That would mean more regular and reliable paychecks. He was in, and he persuaded José to give it a try as well.

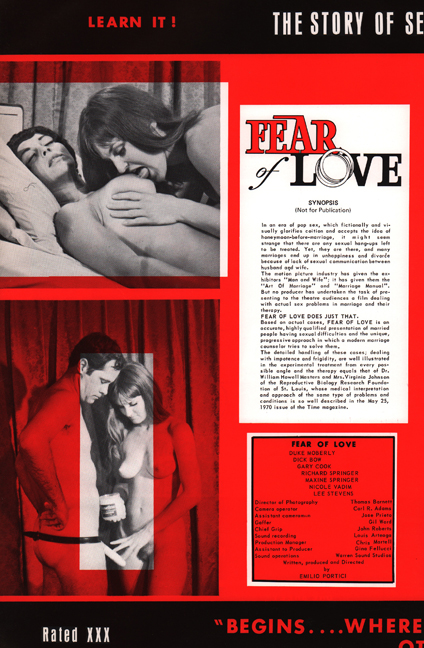

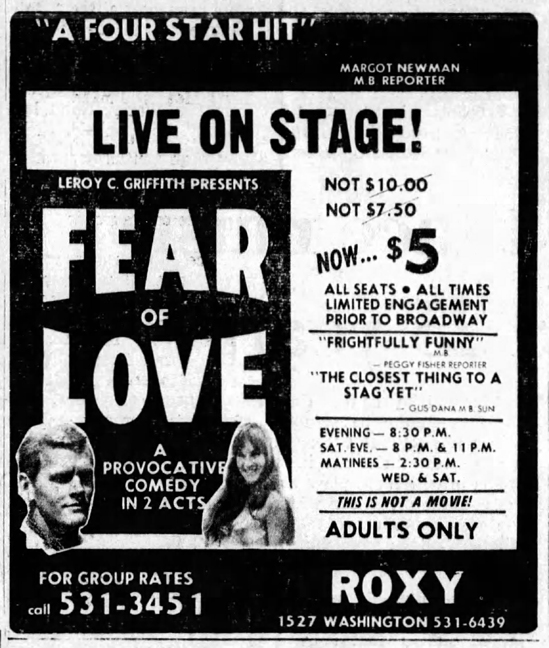

In early 1970, Harvard – using the nom de porn of ‘Emilio Portici’ – made their first feature, Fear of Love (1970). Harvard directed, José shot it, and Rafael, the production manager, corralled the available Cuban film crew from Calle Ocho to help out. It was a cash-in imitation of a recent sex documentary called Man and Wife (1969) which had been hugely successful. ‘Fear of Love’ was a similarly pseudo-instructional tale of marital problems caused by sexual woes that are resolved by a marriage counselor – and it too played well in Leroy Griffith’s adult theaters.

*

3. ‘Fear of Love’ – the Live Show

Leroy Griffith took note of the film’s success, and had an idea: he had a string of former burlesque theaters, so he suggested that Harvard convert the movie into a risqué live performance piece. Griffith even promised he’d finance a theatrical run on the stage at the Roxy, one of his Miami theaters.

Harvard liked the idea, and the stage show opened in September 1970, advertised as “an educational drama in two acts.” The cast included one Barry Bennett, a fresh-faced 25-year-old New Yorker, in the central lead role of the sex counselor. Barry had studied acting at college, and Harvard had taken a shine to the kid, offering him the chance to star in movies soon to be made by his newly-formed company. Barry had just proposed to his girlfriend, and wasn’t sure that sex movies were for him, but he jumped at the chance to have a starring role in this high-profile stage production.

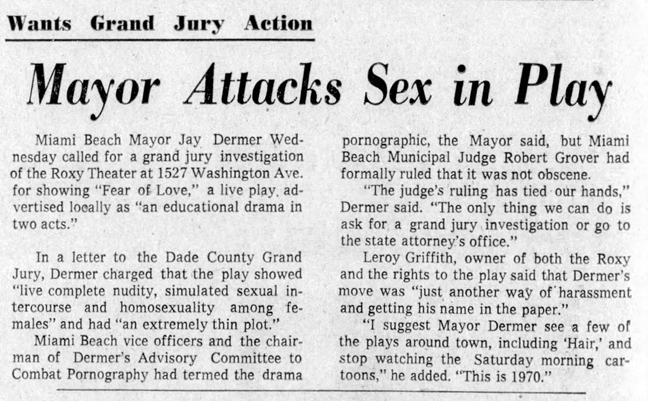

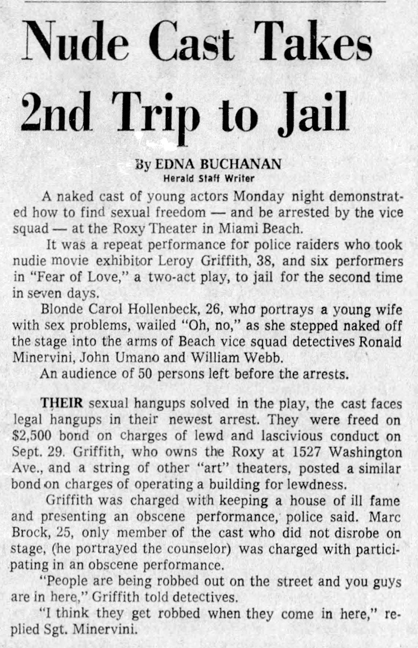

One of the first people in line to see ‘Fear of Love’ onstage at the Roxy was the Miami Beach mayor. He wasn’t impressed. He reacted by writing a letter to the Dade County Grand Jury declaring that the play showed “live complete nudity, simulated sexual intercourse, and homosexuality among females.” As if that wasn’t bad enough, it also had an “extremely thin plot.” At first, it seemed that the play’s run would be allowed to continue as a Miami Beach Municipal Judge ruled that it was not obscene. But then the performance was busted, and Leroy Griffith and six cast members were arrested when they left the stage. They were ordered to get dressed, and taken to Miami Beach police station where bonds were set at $2,500 each. Griffith was booked for operating a building of lewdness, and the actors for lewd and lascivious conduct. Barry Bennett was arrested, even though he was the only actor who didn’t take off his clothes, and he was charged with participating in an obscene performance.

The performance resumed two days later, whereupon the vice squad burst in – and arrested everyone all over again. Griffith protested loudly as he was led away, “People are being robbed out on the street, and yet you guys are in here?!” To which the arresting officer replied: “I think that people are getting robbed every time they watch this performance.”

The result of the legal kerfuffle were two 30-day jail sentences and a $600 fine for Griffith, $300 fines for the naked cast members, and a $150 fine for Barry Bennett. When I spoke with Barry years later, he remembered that it was a serious moment for the cast. They were facing jail sentences for simply acting on stage. In October 1970, Leroy Griffith reluctantly took the play off the schedule, and his theater returned to playing adult films.

As a sidenote: Griffith was getting beaten up from all sides. In 1971, he stopped showing adult films in some of his theaters so that he could exhibit the feature film ‘Che!’ (1969) starring Omar Sharif. It was an intentionally noncommittal version of the Cuban revolution that recounted Che Guevara’s transformation from doctor to political revolutionary in Fidel Castro’s coup. The movie greatly displeased many of the Cubans in Miami, especially those in the filmmaking community who’d worked on Griffith productions – and they retaliated in force. There were bomb threats, physical violence, and even an incident when a Cuban turned up at Griffith’s office brandishing a gun. It was all too much for the theater owner, and so Griffith decided to go back to the safer activity of exhibiting sex films.

*

4. ‘Fear of Love’ – On Tour!

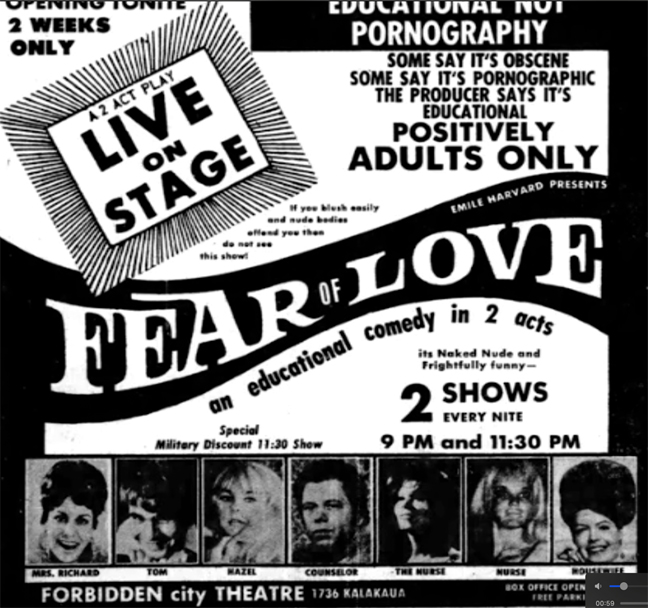

Meanwhile, Emile Harvard wasn’t entirely disappointed at the controversy caused by the ‘Fear of Love’ production: he’d arrived in Miami with a splash, made some money, and was now ready for the next step. Griffith and Harvard felt there was more mileage to be obtained from the stage play so they convinced Jack Cione, owner of the Forbidden City Theater in Honolulu to put on ‘Fear of Love’ in a two-week run starting January 7th, 1971. Harvard flew over to Hawaii, and took some of the same actors from the Florida production, including Barry Bennett.

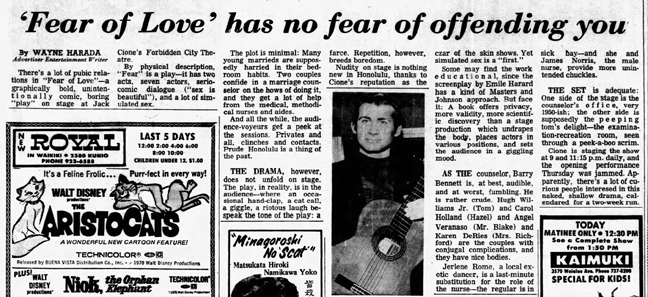

Harvard was smart enough to know he had to play up the play’s socially redeeming features, so he gave interviews in Hawaii claiming that “a group of eight psychiatrists came to see the show and they said they were sorry it couldn’t have been seen on-stage 30 years ago – as it would have saved a lot of marriages.”

But Harvard wanted to have his cake and eat it: when ‘Fear of Love’ opened, billed as “direct from Miami Beach”, it was also described as “a graphically nude work” and “the most shocking we’ve seen.” The campaign worked: ‘Fear of Love’ was a sell-out twice a day for its engagement. It was reviewed in the local newspapers as “a two-act play, seven actors, serio-comic dialogue, and a lot of simulated sex,” and the TV news ran several features on it.

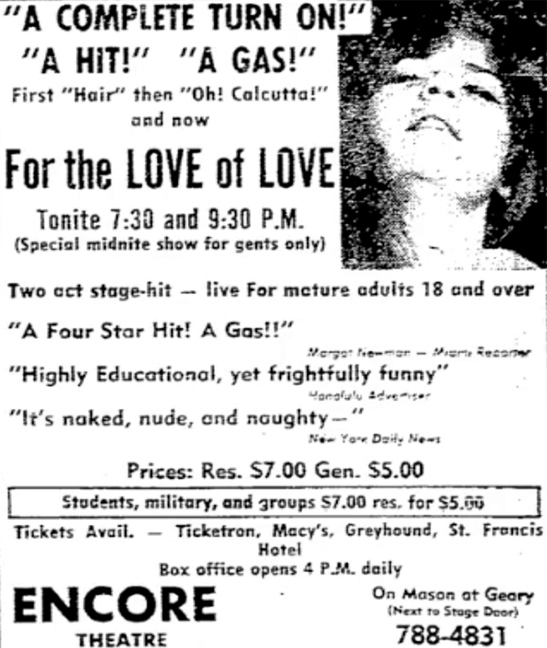

From Hawaii, Harvard took the play to San Francisco when it had a run at the Basin Street West Theater. Harvard heard that the local cops had been tipped off about the play’s run in Hawaii, and they were primed to bust it – so he tweaked the title, calling it ‘For the Love of Love’ in an attempt to throw them off the scent. It was a good idea, but the police were wise to his tricks and the play was busted on opening night, and three of the cast were cited for obscenity. The theater manager panicked and canceled the rest of engagement. Harvard was undeterred and just moved it down the road to the Encore Theater, where it opened in April 1971. Harvard downplayed the hiccup, maintaining that the Basin Street Theater shows had just been rehearsals intended for a private audience.

Once again, Harvard granted interviews to the local newspapers, such as the San Francisco Chronicle, and once again he exaggerated the success of the play, saying that it had played for two months in Miami, seven weeks in Honolulu, and would transfer to Washington DC next. Now he boasted his own experience included “33 years of Hollywood and 122 major feature-length productions, eight television series, awards from the Vatican and the Edinburgh Festival, and a track record that included working with Universal, Paramount, and 20th Century Fox.” He claimed the reason he used a fake name ‘Emilio Portici’ was not because his stage play was pornographic, but rather because he was in the middle of “negotiating a major deal with MGM” and didn’t want to jeopardize it. All the bluster and boasting worked: the stage show was a hit again, and additional midnight performances were added to the twice-an-evening offering.

At the end of the San Francisco run, Harvard decided to retire the play: it had had a good run, but it was expensive to produce, flying and accommodating his actors and crew, and paying for potential legal fees to defend lawsuits. He decided to focus his efforts and money on his fledgling film studio. In mid-1971, he returned to Miami, and dedicated himself to his new activity: making sex films.

*

5. Rafael Remy and Emile Harvard – The Miami XXX Factory

So you may be wondering what this all has to do with Rafael Remy. After all, this is meant to be his story. When Harvard got back to South Florida, he called Rafael, now his go-to film man, and explained the plan – and he wanted Rafael to be his right-hand man.

His business model was simple: with the help of Leroy Griffith, Harvard would finance and produce sex features and shorts that he would send to labs up in New York for processing where they would then be distributed to theaters across the country. Harvard set up a studio at 1238 North Miami Avenue, and formed an inner circle of trusted associates that would deliver an inexpensive, rinse-and-repeat formula that would maximize profits. This small group consisted of Rafael, who would also be production manager, main cameraman, and editor; Jack Birch, a pockmark-faced wannabe actor who had aspirations to be a Jack Palance-style on-screen heavy, and Jack’s girlfriend Carol Kyzer, a quiet, blonde, part-time model who’d done topless layouts for Bunny Yeager; Brad Grinter, a veteran of the horror film scene in Florida who had just made Flesh Feast (1970), a terrible movie whose one claim to fame was its star, 1940s bombshell Veronica Lake; Brad’s son Randy, a 22-year-old who would be Rafael’s assistant; Harvard’s daughter, Esther, who was given the job of office manager; and finally there was Barry Bennett, the young actor who would take the lead performing role in the films.

Carol Kyzer, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Carol Kyzer, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Barry had an additional role – and a critically important one: he was the one who’d take the films to the labs in New York to get the film stock processed and the prints cut. It was a risky assignment: the U.S. Supreme Court still hadn’t come up with an agreed-upon definition of obscenity and so interstate transportation of pornography was a dicey proposition with offenders facing years of imprisonment. But Barry wanted the extra cash that Harvard promised him – so he figured he could deal with the dangers.

Due to the potential illegality of what they were all doing, most of the group took different names to mask their involvement: Harvard reverted to his ‘Emilio Portici’ identity, Rafael Remy became ‘Roberto Raphael’ – if he had a credit at all, Brad and Randy Grinter used any name – just as long as it wasn’t theirs, and most of the time it wasn’t, Jack Birch had a variety of Western-macho names like ‘Jack Colt’ or ‘Michael Powers’, Carol Kyzer became ‘Carol Connors’, a name that she would use for the next decade, and Barry Bennett took the name ‘Marc Brock.’ Harvard would be the nominal director of the films, but in practice, he would share the responsibility with Rafael.

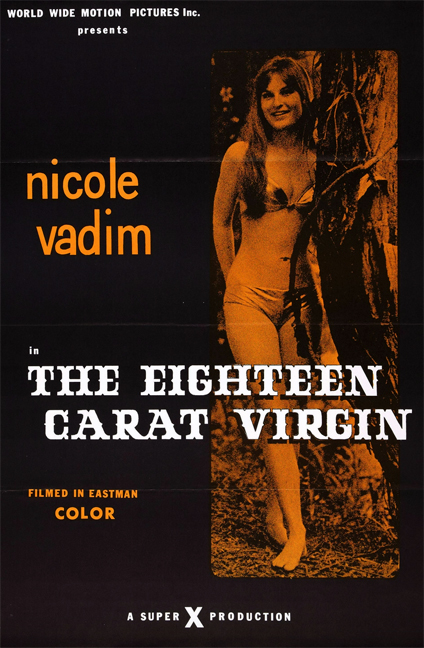

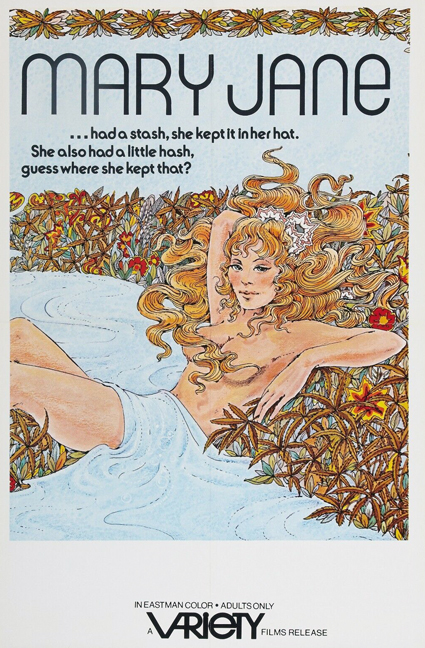

For the next three years, Harvard’s studio churned out sex films on a regular basis: titles like Penny Wise (1970), The Good Fairy (1970), The Eighteen Carat Virgin (1971), Mary Jane (1972), Your Neighborhood Doc (1972), School Teachers Weekend Vacation (1972), and Female Stud Service (1972). Most of them were made according to a template loosely agreed with Leroy Griffith: each feature film would be roughly 65 minutes long, and would cost less than $15,000. Most were shot in Harvard’s small studio at 1238 North Miami Avenue, though they would occasionally venture out into fancy houses like a Coconut Grove mansion belonging to a friend of Harvard, Sepy Dobronyi.

Nearly all of them starred Barry Bennett, who, as ‘Marc Brock’, quickly became Florida’s leading male porno star. He wasn’t the most charismatic performer you’d ever seen but he could be relied upon to use his improv and comedy skills to fill the holes in the scripts. Many of the movies also featured Jack and Carol, who soon became a married couple.

All the films did ok but none were spectacular. Rafael worked hard behind the scenes, and nearly all of the crews consisted of his old Cuban friends, including José Prieto who came onboard for an occasional job. Randy Grinter remembers Rafael telling him that the softcore sex film business In Florida had been built by Cubans, and now it was Cubans who were responsible for the hard-core films too.

And then in 1972, Deep Throat became a national smash-hit: it had cost $25,000 and had made several millions for the New York mob that distributed it. It was essentially a New York film: the financing came from the Brooklyn-based Peraino family, and the director, stars, and crew were mostly New York-based. But Emile Harvard didn’t view it that way: ‘Deep Throat’ was shot in Miami, making ample use of the exteriors and locations that he normally used like Sepy Dobronyi’s pad, and two of his featured players, Jack and Carol, both had roles in it. For someone who had labored for the previous two years to make money in the business, Deep Throat’s wild success felt a kick in the teeth to Harvard. He was mad and resolved to get even. Crew members who worked with him remember him shouting, in his thick eastern European accent, about the fact that the success should have been his. Harvard reacted swiftly, increasing production, widening his distribution, and expanding his business: the least he could do was to cash in on the new bigger market that ‘Deep Throat’ had created.

*

6. XXX, after ‘Deep Throat’ (1973)

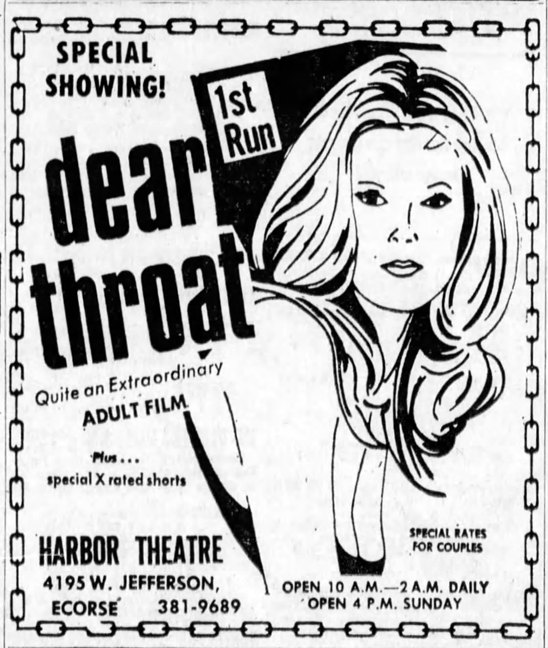

Emile Harvard and Leroy Griffith were strange bed-fellows, but their relationship was symbiotic and so they had regular contact about the sex film market – and how to exploit it. For example, Griffith suggested ripping off ‘Deep Throat’ by making a movie called Dear Throat (1973) saying that people would see the ads in the newspapers but not realize that they were two different films with similar names. Harvard obliged, making a cheap knockoff starring, who else?, Marc Brock and Carol Connors. It was blatant plagiarism, and so Harvard used a different name for the film – P. Arthur Murphy – fearing reprisals from the mob owners of ‘Deep Throat.’ It was one of an increasing number of different identities he started to use, as the legal heat increased around adult films. Thirty years after the war in which he’d hidden his identity to work undercover, Harvard still seemed incapable of living a simple life as himself.

Not that he’d grown afraid of publicity: Harvard gave a number of interviews to newspapers and magazines. In one of them, he used the name ‘Bruno’ – much to the amusement of the Cuban crews. One interview quoted ‘Bruno’ (“in a guttural European accent”) as someone who “used to be big in Hollywood” and that he was “only turning out this stuff between engagements.” The reporter was even invited to Harvard’s studio where he reported that all the technicians were Cuban, and that “Bruno’s studio contains, as scenery, an office desk, a couch, and a bed: the three essentials for a porno movie.” While he was there, Bruno warned him not to speak loudly as he was making a “quality movie” and the actors “are very sensitive about what they have to do.”

Harvard may have been unhappy about missing out on the ‘Deep Throat’ deep cash, but he was still doing pretty well – a fact that was evident to many of the Cuban crew, as one of them remembered: “Emile was a very different guy to us Cubans, but he liked us and always had work for us. He paid by the hour in cash at the end of each day, but we never hung out with him or anything like that. And we could all see that he was making big money.”

It was true: Harvard made no attempt to hide a pretty luxurious lifestyle – he lived on Palm Island, a man-made development, situated between the city of Miami and its glamorous suburb of Miami Beach. The area was famous for its celebrity residents, and neighbors had included gangsters Al Capone and Meyer Lansky, and the non-gangster, TV presenter Barbara Walters. Harvard drove to work every day from his large house in a new cherry-red Buick Centurion, and often talked about eating at Miami’s finest restaurants. It may have irritated some of the Cubans who worked for Harvard, but Rafael Remy was happy. As Harvard’s number two, he was faithful to a fault, despite the difference in the money they were earning. Rafael had become the glue who held everything together and he kept people happy. He ran a tight ship, making sure they had a right-sized team for every shoot, choosing actors and crew carefully, and making sure everyone was paid.

In 1973, Harvard confided in Rafael that he felt fatigued. Worse he’d started feeling pain in his joints and bones. He figured he was just getting old – he’d recently turned 60 – and said he wanted to take a step back and delegate more of the filmmaking to the others, like Rafael himself, Marc Brock, and Jack Birch.

When I spoke to Brock many years later, he remembered the change in how Harvard operated: “Emile was a control freak, and then all of a sudden, he handed the reins over to the rest of us, and so we started to alternate the directing duties.”

*

7. ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973) – and the (next) Cuban Rebellion

In October 1973, Harvard got Marc Brock to shoot his latest film, Daddy’s Rich. Marc was a reliable sex performer, having appeared in most of Harvard’s features and loops, but the Cubans on the crew knew he was a sloppy operator, being regularly picked up by the cops for petty misdemeanors like shoplifting, a small stash of weed, and minor DUIs. Marc put together a rough budget for the movie, but it was higher than normal. The film wasn’t materially different from the rest of Harvard’s efforts, but somehow Marc convinced a distracted Harvard that he needed more money this time.

For a start, there were ten crew members – more than double the normal number – and there was an inflated cast of nine. Then there was the location: Marc arranged with Sepy Dobronyi that they would shoot most it in the same Coconut Grove house where ‘Deep Throat’ had been shot the previous year. Rafael argued with Marc that there was no need for the exterior location, but Marc was adamant. And then Marc withheld payment from the Cuban crew after the first day. Harvard had always treated everyone fairly and so the crew were suspicious Marc promised that everyone would be paid the following day, but the Cubans were unconvinced, a clash erupted, and they nearly came to blows.

Sepy Dobronyi’s house, venue for the filming of ‘Deep Throat’ (1972)… and ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973)

Sepy Dobronyi’s house, venue for the filming of ‘Deep Throat’ (1972)… and ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973)

One of the crew that I spoke to years later remembered what happened next: “One of the guys, a grip on the shoot, took exception at Marc Brock after that – big time,” he said. “This grip was a new guy, and he was a hothead who liked to overreact. Next day, when the grip didn’t show, I called him up, and he just said, ‘Fuck Brock’. When I told him to do the right thing and come to the set, he threatened to call the cops and tell them about the shoot. We didn’t really believe him but we kept an eye out for the police that day.”

Sure enough, halfway through filming, Rafael noticed a cop car slowly coming up the road towards the house. He shouted in Spanish “Get the hell out of here now!”, and the crew scrambled their equipment together, much to the confusion of the semi-clad actors. Remarkably all eight crew on set that day made it out over the rear hedge, and down the lane, where they jumped into cars and fled the scene. They left Marc with Stan, his assistant director, as well as six actors, in the house – who were all arrested. Marc and Stan were charged with manufacturing obscene material, while the actors were charged with lewd and lascivious behavior, and indecent exposure. Sepy Dobronyi, the owner of the house, wasn’t helpful, making a statement to the newspapers that he was playing tennis at a nearby park at the time – and that the actors had broken into his home at which point his house guests had called the police.

Harvard, fearful of negative publicity for his business, called Leroy Griffith for help. Griffith snapped into action dispatching his main attorney, Alan Weinstein, to the precinct. Weinstein had been getting Griffith out of scrapes for years, including helping out when ‘Fear of Love’ had been shut down. Weinstein got everyone out of jail – and threw in an indignant statement to the press: “The police had no right to be on the premises,” he said. “There were more cops involved in arresting people taking pictures than there are on a murder case. Someone’s priorities are out of whack.”

The arrests caused a mini-media storm in the Miami newspapers, and for a few months, Harvard had to curb back his movie production schedule. Harvard blamed Marc Brock: he’d once viewed Brock as a protégé and an investment for the future, and so he’d ignored Marc’s legal indiscretions because he was essential in transporting the films up to the labs in New York, as well as being a reliable performer in front of the camera, but Harvard had had his fingers burned by this.

When Harvard looked into the finances of the film and saw that Marc had been using the inflated budget to line his own pockets, pilfering money for himself, he called Marc and told him he was fired.

*

8. Trouble in Wonderland

By 1974, it seemed that the immediate hardcore boom after ‘Deep Throat’ was starting to subside, and some of the players who’d been involved were looking to go legit – or at least, go more legit than being underground producers of hardcore smut.

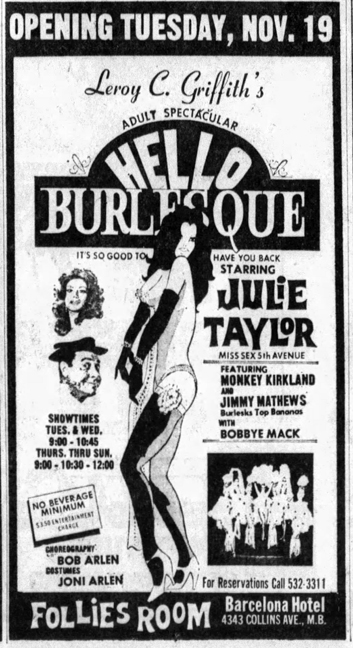

Leroy Griffith still played Harvard’s XXX films in his theaters as a cash cow source of income, but he was branching out in other directions. For one thing, he decided to revive the burlesque variety shows that he’d pioneered in Miami in the 1960s, this time opening a big production, ‘Hello Burlesque’ in Miami Beach with strippers, comedians, and music acts.

Harvard was looking to diversify too. He’d acquired theaters of his own, including the Cameo at 1445 Washington Ave, and when he and Rafael Remy had to put their sex films on hiatus, they decided to make a different kind of film. Or as Harvard bellowed one day, “Let’s make a serious movie!”

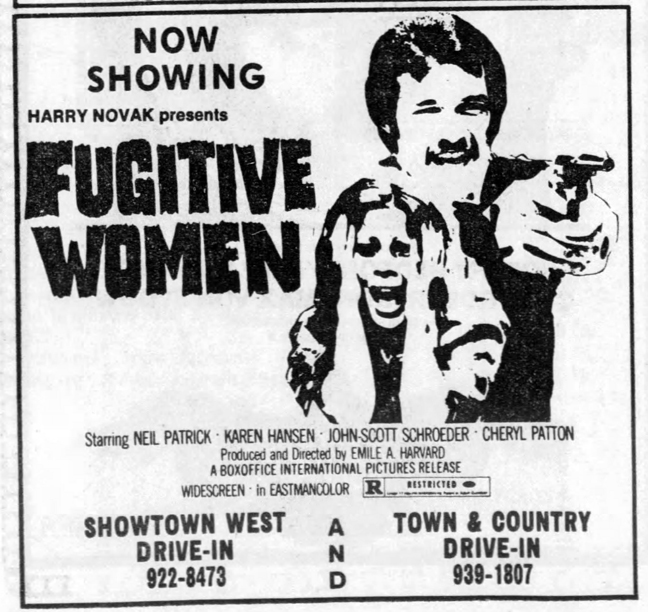

Harvard’s daughter, Esther, had written a sensitive script called ‘Of Gentle Heart’ about an escaped convict who befriends a young boy. It was originally intended as a touching character study, but when Harvard got his hands on it, he couldn’t help himself. His exploitation instincts returned, and he renamed it Fugitive Killer (aka Fugitive Women) (1974). Rafael was on hand as always to oversee the production.

When the film was released, after a gentle opening on a wholesome and bucolic farm, it turned into a rape and murder exploitation film. Marketed with the catchphrase, “Once he started, he couldn’t stop! If he didn’t rape you, he killed you,” the film was a bizarre mess, and despite being distributed by Harry Novak’s Boxoffice International Pictures, Inc., it failed to raise much interest.

It turned out that the film’s lack of success was the least of Harvard’s concerns. They say that bad news comes in threes, and it was certainly true for Harvard in 1974. He’d already scaled back his sex film production as a result of the bust of ‘Daddy’s Rich’, when he lost his son, Roy, who died after a short illness. Then, Harvard received an explanation for the fatigue and pain he’d been experiencing: he was diagnosed with bone cancer. He began treatment immediately, and told Rafael they had to put all filmmaking on hold.

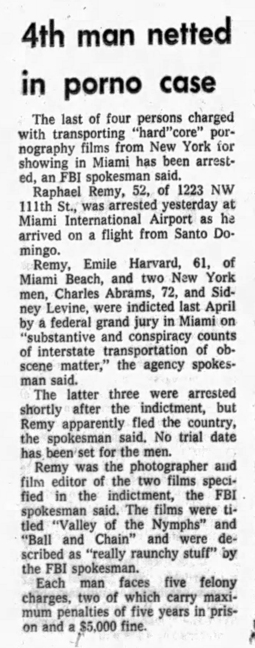

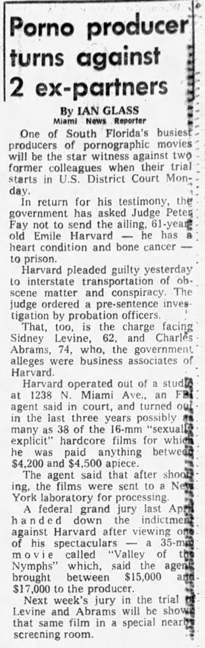

Another surprise awaited him though. In April 1975, the FBI turned up at his front door to arrest him: they’d been tipped off by a source that Harvard had been transporting pornographic films between Miami and New York. Two films were specified in the indictment: ‘Valley of the Nymphs’ and ‘Ball and Chain’, which were described by the FBI spokesperson as “really raunchy stuff.” Harvard faced five felony charges relating to “substantive conspiracy counts of interstate transportation of obscene matter,” two of which carried penalties of five years in prison.

Arrest warrants were issued for three other people: two of them were Harvard’s New York associates, Charles Abrams and Sidney Levine, who had taken delivery of the films over the years when Marc Brock smuggled them into the city. Both Abrams and Levine were taken into custody.

But the final arrest warrant was for Rafael Remy – except that Rafael got away. Somehow, after Harvard was arrested, he got word to Remy and told the Cuban of his arrest. Remy drove straight to Miami airport and left the country, flying to Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, to avoid the Feds catching up with him.

What nobody realized – not Harvard nor Rafael – was that the FBI source, the person who had alerted the authorities to Harvard’s pornography operation, was actually Marc Brock. After Brock had been arrested on the set of ‘Daddy’s Rich’ – and then fired by Harvard, he’d panicked. He already had a string of minor arrests to his name, and now feared that this time the judge would throw the book at him. So Brock decided to get his revenge on Harvard, and bought some protection for himself, by spilling the beans on how Harvard’s sex film business worked. Brock laid out how he personally shipped films to the New York labs, where prints were struck and shipped to theaters across the country. In return for singing, Brock was granted immunity from prosecution.

Three months later, Remy tried to slip back into Miami. He didn’t want to involve family, so he needed someone to stay with. Of all the people he could have contacted, he called Marc Brock, unaware that Brock was working with the FBI. And so, when Remy landed at Miami airport, they were waiting for him. An additional charge of fleeing arrest was added to Rafael’s woes.

As for Harvard, he was understandably nervous: he was the ringleader and owner of the business, the man controlling all the moving parts, and the mastermind behind the operation. So he did what he always did when he was in a bind: he hustled. Harvard told the Judge that his bone cancer was terminal, and that jail time would be dangerous to his health. He said that the real criminals were actually the two aging New Yorkers, Abrams and Levine. They were the ones who distributed the films far and wide, whereas he was just a cog in the machinery. In short, Harvard pleaded guilty and offered to testify for the government. The Judge consented, and Harvard was set free.

After a life of bluffs, double bluffs, and downright lies, this time Emile Harvard was telling the truth about his health. His bone cancer quickly got worse, and in 1976, his health deteriorated. He died that August.

Rafael Remy was eventually let off when the charges against him were dropped. Marcy Bichette, the daughter of his old friend Dolores Carlos, had put on a rock show to raise some money for his legal costs which made the ordeal easier.

But he was now in his early 50s, and he’d had enough. Within the previous two decades, he’d gone from having a promising career in films in Cuba, working on global productions like ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ (1958) and ‘Our Man in Havana’ (1959) to fleeing Cuba to escape Castro’s revolution, and ultimately making a home in Florida sex films – all the way from the softcore tease days to now being arrested for hardcore films. He often joked that he couldn’t escape the fortune teller’s prediction that had foretold trouble and strife for him, but he consoled himself that he’d lived a full life. Now he wanted the easy life.

*

9. Aftermath

And so, the late 1970s marked more or less the end of the roads for the band of Cuban filmmakers who had revolutionized sex filmmaking in Florida.

Dolores Carlos was living a quiet life still working in the bank, married, and with a new family. Her daughter Marcy toured with her band Bitter Sweet, until, by 1981, when the travel and late nights became too much. She’d been on the road for years, hadn’t had a break, and the lounge scene was dying. Marcy was 30, and figured it was time to accept that the acting and music dreams were over. She found a place in Miami not far from Dolores, and they remained close seeing each other often. Later on, they would go see Marcy’s step-brother, Dante Bichette, play baseball when his team came to Florida. Dante was an outfielder for various teams, and was a four-time All-Star and contender for the Most Valuable Player Award in Major League Baseball.

Marcy and Dolores, early 1990s

Marcy and Dolores, early 1990s

Marcy got work as a bartender, giving much of her spare time – and money – to local animal rescue centers. In 1983 she got married. The guy developed a drug problem, and though she stuck around for three years, his habit effectively ended the marriage. They divorced, and she never saw him again.

From time to time, Dolores hosted reunions for the old Cuban gang, and they’d get together and swap stories. Gradually the reunions became fewer and less well-attended as one-by-one the various friends died.

K. Gordon Murray, the exploitation film man, known for re-dubbing and re-releasing foreign fairy tale films for U.S. audiences, and who’d been the first person who had trusted Dolores as a potential filmmaker, ended up getting into trouble with the Internal Revenue Service. They seized his films and took them out of circulation. Murray protested his innocence, but the case dragged and, in 1979, before it could come to a conclusion, he died of a heart attack.

As for Manuel Conde, after leaving Florida in the 1960s, he settled in California where he embarked on another stage of his sex film career by producing and directing hits such as The Danish Connection (1974), Deep Jaws (1976), and The All-American Woman (1976). By the early 1990s he’d developed dementia and he died in 1992.

José Prieto and Raphael Remy, the two inseparable Cuban friends who’d escaped their homeland after Castro’s takeover, both passed – Raphael, relatively young at 60 years of age, in 1984, while Prieto died an old man, two decades later.

In 1996, Dolores became sick and was diagnosed with cancer. The first person she told was Marcy. Marcy was heartbroken, but she immediately called each family member to tell them the news. At first the signs were good, and doctors hoped they had caught everything in time, but it was a false hope. It was a painful, drawn-out process, and Marcy did everything she could to make it easy for her mother. The family rallied – one family member admitted they all pulled together for Marcy’s sake as much as anyone else – but it was to no avail. Dolores died in January 1997. She was 66.

*

10. Endgame

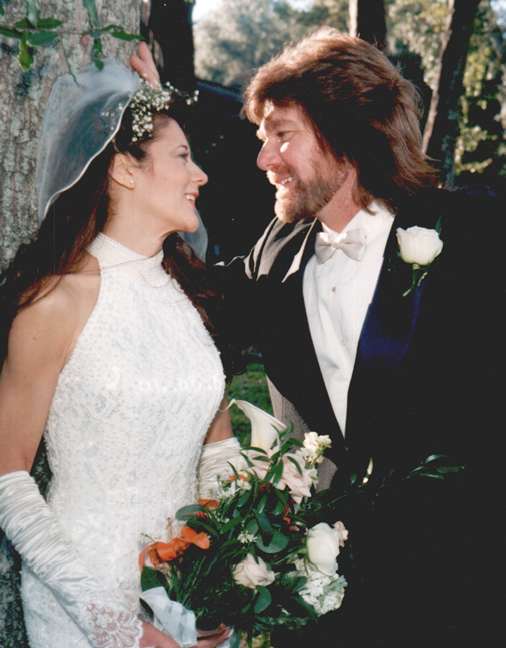

In 1999, Marcy married her boyfriend, Tom Flynn. They’d met a few years before, and their first date was going to midnight mass with Tom’s mom. They become inseparable: Marcy had found the relationship she’d always wanted. She stopped bartending so she wasn’t out at night and could spend more time with Tom. She took up a new career – perhaps the one to which she was best suited of all: she became a pet stylist and groomer.

Tom had proposed to her at the Hollywood Beach Hotel in Miami. The venue was significant: Tom’s parents had met there when they’d both been employed by the hotel years before. Not only that but it was also where Tom had been conceived when his folks had taken refuge in one of the rooms during Hurricane Diana, a fierce tropical storm back in 1960. The hurricane happened to hit Miami the night of Marcy’s tenth birthday. So it made sense that their wedding took place there as well.

Marcy and Tom spent the next two decades happily married in South Florida. Tom knew a little about Marcy’s films, and sometimes asked about her past but she didn’t talk about it much. The present and the future were more important to her. Marcy did appear in another film, ‘Marley and Me’ (2007) with Owen Wilson, where she had a fleeting, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it walk on part.

And then three years ago, Marcy was diagnosed with colon cancer, the same that Dolores had. Marcy passed away in May 2021 at the age of 70. She was cremated and her ashes scattered at, where else, Hollywood Beach Hotel, where she and Tom had got engaged and married.

I took Tom out for dinner recently and told him some of the stories I’d learned about Marcy, her mother Dolores, and the people they’d known and worked with. He was surprised to find out about it all, and shook his head in sad happiness hearing stories about her. Most of all though, he just missed Marcy. “I always wonder what I did in a previous life to deserve her,” he said. “I must’ve done something right somewhere along the way. She was a good person, and she was chasing butterflies to the very end.”

*

Postscript

The United States has always been a nation of immigrants – some of whom, like the Cubans in this series arrived in the country fleeing from adversity. The vast majority have helped drive business creation, fuel innovation, and fill essential workforce needs, all core principles of American values. Their stories are often overlooked, but worse, all too often they’ve been maligned and mistreated. I’m an immigrant, and at the naturalization ceremony, the presiding officer will tell you that now you have become an American, the most important thing you can do is to hold onto where you’ve come from: the culture, the customs, the food, and the way of life. If you can do that, you’re told, you’ll be preserving what truly makes America great. You’ll be keeping this a nation that is welcoming of differences, diversity, and inclusion.

People like Dolores Carlos, Manuel Conde, José Prieto, and Rafael Remy who came to this country, and chased butterflies of their own.

*

*

The post Chasing Butterflies: Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida – Part 4, Rafael Remy’s Story – Podcast 148 appeared first on The Rialto Report.

180 odcinków

Manage episode 449419055 series 2414495

Previously on Chasing Butterflies – Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida:

After Dolores Carlos’ retirement from acting in South Florida nudie films in the late 1960s, she still remained close to her circle of Cuban filmmaker friends, and none more so than José Prieto, Greg Sandor, and Rafael Remy. They would still meet regularly, and all three took an active interest in her daughter Marcy’s well-being. From time to time, they would joke about the fortune teller that the three men had consulted when they escaped from Cuba. Greg Sandor had moved out the California and had indeed found the money and respect that had been predicted for him. Similarly, José Prieto had found a degree of fame and notoriety following the success and outcry that followed the release of films he made, such as Shanty Tramp (1967) and Savages from Hell (1968). The only exception to the mystic’s forecast was Rafael Remy: he’d fared well and was not seeing the trouble and strife that had been foreseen in his future.

Rafael had lived a lower profile existence but with more regular work than his two friends: due in part to his jack-of-all-trades skill-set and willingness to get involved in anything, he was always in demand. He was a cameraman, editor, lighting, gaffer, soundman, and production manager who was cheap and could always be relied on to deliver a decent job.

But as the 1960s turned into the 70s, the film business was changing: the innocent exploitation films that had greeted them when they arrived from Cuba were giving way to more explicit sex movies whose legality was questionable, and Rafael was suddenly being offered an altogether different kind of job.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many people involved in the Florida film business of the 1960s and 1970s. Their overlapping personal histories reveal an untold chapter of adult film history – and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it. These are some of their stories.

This is the concluding episode of Chasing Butterflies, Part 4: Rafael Remy’s story.

You can listen to the Prologue: Dolores Carlos’ story here, Part 1: Manuel Conde’s story, Part 2: José Prieto’s story, Part 3: Marcy Bichette’s story.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Leroy Griffith, Veronica Acosta, Marcy Bichette, Mikey Bichette, Lousie ‘Bunny’ Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Manny Samaniego, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Herb Jeffries, Tempest Storm, Chester Phebus, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Lynne O’Neill, Something Weird Video, and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 45 minutes long.

*

1. Rafael Remy, the fortune-teller’s prediction – and Emile Harvard

In the late 1960s, Rafael received a called from someone called Emile Allan Harvard.

In a strong Eastern European accent, Harvard explained that he was new to Florida and was looking for a film man: someone who knew how to put a movie together, someone who knew where to find actors, crew, locations, and equipment. Harvard had heard that Rafael could be the man to assist him, and that Rafael was a man with expertise who’d built an extensive network of contacts in the years since he’d arrived penniless from Cuba. But Rafael was wary: he asked around about this new arrival in the state, but could find no one who knew anything about Harvard.

Rafael was right to be cautious: Harvard was a mysterious hustler with an unusual history. Emile Harvard was a Romanian Jew, who’d started his adult life in 1930s Bucharest training to be a cameraman. And then in the build-up to World War 2, Harvard became a spy for the British. It was a volatile period in Romania as the country’s fascist dictatorship was aligned to Nazi Germany and the government was suppressing any opposition by force. Despite the dangers, Harvard loved the subterfuge. He was given a cover profession to conceal his espionage activity which was to be a newsreel cameraman for British Movietone News. He used these media credentials to gain access to key government sites and report on them to his British paymasters. It was a perilous assignment, but one he performed with alacrity.

Romania was a key supplier of the oil for the Nazi war effort and so he also gathered information on the refineries and transport routes. Then he captured footage of Romanian military operations, like airfields and supply depots. But Harvard never seemed happy doing the same activity for long, and soon he was suggesting ways that he could sabotage Nazi efforts. His motivation was less born out of deeply-held ideological convictions, but rather out of a love of excitement and intrigue. A later acquaintance described Harvard as “an enigma, rather than a real person, a shady, shape-shifting person with many identities, a man who you felt you could never truly know.”

The useful life of a spy is a limited one – and in 1943, his cover was blown when Harvard apparently blabbed to someone he shouldn’t have and was reported to the authorities. Life In Romania was suddenly impossible for him so his British employers moved him to Tel Aviv, a city then in British-administered Mandatory Palestine, where he got married and had a daughter, Esther.

When the war ended, Harvard obtained Israeli citizenship before moving to Canada, first Montreal, then Toronto, where he started a career as a TV producer and director. He formed several small-time companies, including Harvard Productions, ostensibly to make television series for the American market. His wartime activity may have been over, but in truth Harvard still enjoyed living a partly fictional life, and with each career move, he inflated the achievements on his resumé which he generously shared with the press. He frequently spoke about working for MGM for twelve years, producing content for NBC, CBS, and Pathé, and having a successful career in Hollywood – none of which was true.

A few years later, without any major credits to his name, Harvard decided on a radical change of direction: after a vacation to see his brother in Miami, Florida in 1960, he was inspired to announce that Harvard Productions was planning a Florida-themed club in Toronto to be called ‘Oceans 11’, after the Rat Pack movie that had hit the cinemas that year. It was to be an exclusive, high-end, rich-members-only place, which he described as a “health and entertainment” club. The Florida theme meant palm trees, a glass sun-roof, a 500-seat restaurant, nightly entertainment, and a swimming pool with a state-of-the-art wave machine – all to be housed on the top three floors of a Toronto office building. “It will be just like Miami Beach,” Harvard told the newspapers, who lapped up the project with excitement filling pages of breathless newsprint. It was ambition on a grand scale, the kind that comes from someone with a big imagination, not to mention someone whose own money is not at stake. Sure enough, the project failed when it was the funding failed to materialize, and so for Emile Harvard and Harvard Productions, it was back to square one.

Just like the wartime spy Harvard had been, the next years were spent donning various different identities and promoting different business schemes. Some seemed serious, others were harebrained. They included hawking time-share properties, selling Jacuzzis, and offering dubious healthcare products (“at last a cure from embarrassing itching!” read the copy for one innovative cream.) Perhaps part of his success came from his appearance: Harvard was a tall, distinguished, and earnest-looking man who projected intelligent seriousness. But in 1967, Harvard was in the news again, this time posing as a doctor, prescribing Belltone hearing aids, and persuading pensioners to sign up for exorbitantly-priced payment plans. He was arrested and charged for his involvement in the fraudulent scheme.

Each time he was embroiled in a scandal, Emile Harvard somehow managed to wriggle out, and re-emerge a year or two later involved in another dodgy deal. The irony was that he was never afraid of the media. Quite the opposite: he was first in line to give newspapers interviews and quotes, just as long as they spelt his name correctly.

*

2. Emile Harvard and ‘Fear of Love’ (1970)

And so, in the late 1960s, on the lam from his latest scam, Harvard turned up in Miami, in his early 50s, with his wife and two teenage children. This time he decided to return to his first love – filmmaking. A cursory glance at the local theater scene in South Florida convinced him that he needed to speak with the most powerful and influential player in town – and that was Leroy Griffith.

Griffith’s theater business had come a long way since he moved to Miami in the early 1960s and bought the Paris Theater staging burlesque shows with Tempest Storm before meeting Dolores and moving into the sexploitation movie business with men like Manuel Conde. By the early 1970s, Griffith’s empire had grown to 12 adult theaters, including the Paris, Roxy, and Gayety theaters, and 15 adult book stores in the area, and he claimed to have produced 30 softcore adult films too. By now, Griffith was a well-known figure in Miami, though he was at pains to point out, in an interview in 1969, that he made films that specialized in ‘nudity’ and not ‘exploitation.’ ‘Exploitation’, he explained carefully, referred to “torture, fetishes, and lesbianism”, subjects that he just wouldn’t touch.

Griffith was intrigued by Emile Harvard: here was an older, seemingly sophisticated European, who boasted of a successful Hollywood career and wanted to make films for him to exhibit. Griffith told Harvard to speak to José Prieto and Rafael Remy, two men who would give him a crash course download in Florida low-budget filmmaking. So Harvard did, and came away impressed with both the Cubans’ experience. But Harvard explained he wanted to make a different kind of flick. He didn’t want to join the crowded field of slasher films, biker movies, or nudie-cuties: he wanted his films to go further and push the envelope. In short, he wanted to put sex up onscreen. Real sex, sex that happened before your very eyes. Harvard formed a company, set up a small office, and offered José and Rafael in-house jobs working on his upcoming sex film projects.

José was unsure. He didn’t seek film work as much as Rafael, happy to pick up temp jobs outside of the movie business when he needed money and wait for movies that interested him. He also wasn’t sure about making more explicit sex films. They were still illegal, right? He’d had enough of hiding and fleeing from government interest, and now he preferred to keep his head down and enjoy a quiet life. But Rafael felt differently. This could be a new income stream: the films would be cheap, so there would be more of them. That would mean more regular and reliable paychecks. He was in, and he persuaded José to give it a try as well.

In early 1970, Harvard – using the nom de porn of ‘Emilio Portici’ – made their first feature, Fear of Love (1970). Harvard directed, José shot it, and Rafael, the production manager, corralled the available Cuban film crew from Calle Ocho to help out. It was a cash-in imitation of a recent sex documentary called Man and Wife (1969) which had been hugely successful. ‘Fear of Love’ was a similarly pseudo-instructional tale of marital problems caused by sexual woes that are resolved by a marriage counselor – and it too played well in Leroy Griffith’s adult theaters.

*

3. ‘Fear of Love’ – the Live Show

Leroy Griffith took note of the film’s success, and had an idea: he had a string of former burlesque theaters, so he suggested that Harvard convert the movie into a risqué live performance piece. Griffith even promised he’d finance a theatrical run on the stage at the Roxy, one of his Miami theaters.

Harvard liked the idea, and the stage show opened in September 1970, advertised as “an educational drama in two acts.” The cast included one Barry Bennett, a fresh-faced 25-year-old New Yorker, in the central lead role of the sex counselor. Barry had studied acting at college, and Harvard had taken a shine to the kid, offering him the chance to star in movies soon to be made by his newly-formed company. Barry had just proposed to his girlfriend, and wasn’t sure that sex movies were for him, but he jumped at the chance to have a starring role in this high-profile stage production.

One of the first people in line to see ‘Fear of Love’ onstage at the Roxy was the Miami Beach mayor. He wasn’t impressed. He reacted by writing a letter to the Dade County Grand Jury declaring that the play showed “live complete nudity, simulated sexual intercourse, and homosexuality among females.” As if that wasn’t bad enough, it also had an “extremely thin plot.” At first, it seemed that the play’s run would be allowed to continue as a Miami Beach Municipal Judge ruled that it was not obscene. But then the performance was busted, and Leroy Griffith and six cast members were arrested when they left the stage. They were ordered to get dressed, and taken to Miami Beach police station where bonds were set at $2,500 each. Griffith was booked for operating a building of lewdness, and the actors for lewd and lascivious conduct. Barry Bennett was arrested, even though he was the only actor who didn’t take off his clothes, and he was charged with participating in an obscene performance.

The performance resumed two days later, whereupon the vice squad burst in – and arrested everyone all over again. Griffith protested loudly as he was led away, “People are being robbed out on the street, and yet you guys are in here?!” To which the arresting officer replied: “I think that people are getting robbed every time they watch this performance.”

The result of the legal kerfuffle were two 30-day jail sentences and a $600 fine for Griffith, $300 fines for the naked cast members, and a $150 fine for Barry Bennett. When I spoke with Barry years later, he remembered that it was a serious moment for the cast. They were facing jail sentences for simply acting on stage. In October 1970, Leroy Griffith reluctantly took the play off the schedule, and his theater returned to playing adult films.

As a sidenote: Griffith was getting beaten up from all sides. In 1971, he stopped showing adult films in some of his theaters so that he could exhibit the feature film ‘Che!’ (1969) starring Omar Sharif. It was an intentionally noncommittal version of the Cuban revolution that recounted Che Guevara’s transformation from doctor to political revolutionary in Fidel Castro’s coup. The movie greatly displeased many of the Cubans in Miami, especially those in the filmmaking community who’d worked on Griffith productions – and they retaliated in force. There were bomb threats, physical violence, and even an incident when a Cuban turned up at Griffith’s office brandishing a gun. It was all too much for the theater owner, and so Griffith decided to go back to the safer activity of exhibiting sex films.

*

4. ‘Fear of Love’ – On Tour!

Meanwhile, Emile Harvard wasn’t entirely disappointed at the controversy caused by the ‘Fear of Love’ production: he’d arrived in Miami with a splash, made some money, and was now ready for the next step. Griffith and Harvard felt there was more mileage to be obtained from the stage play so they convinced Jack Cione, owner of the Forbidden City Theater in Honolulu to put on ‘Fear of Love’ in a two-week run starting January 7th, 1971. Harvard flew over to Hawaii, and took some of the same actors from the Florida production, including Barry Bennett.

Harvard was smart enough to know he had to play up the play’s socially redeeming features, so he gave interviews in Hawaii claiming that “a group of eight psychiatrists came to see the show and they said they were sorry it couldn’t have been seen on-stage 30 years ago – as it would have saved a lot of marriages.”

But Harvard wanted to have his cake and eat it: when ‘Fear of Love’ opened, billed as “direct from Miami Beach”, it was also described as “a graphically nude work” and “the most shocking we’ve seen.” The campaign worked: ‘Fear of Love’ was a sell-out twice a day for its engagement. It was reviewed in the local newspapers as “a two-act play, seven actors, serio-comic dialogue, and a lot of simulated sex,” and the TV news ran several features on it.

From Hawaii, Harvard took the play to San Francisco when it had a run at the Basin Street West Theater. Harvard heard that the local cops had been tipped off about the play’s run in Hawaii, and they were primed to bust it – so he tweaked the title, calling it ‘For the Love of Love’ in an attempt to throw them off the scent. It was a good idea, but the police were wise to his tricks and the play was busted on opening night, and three of the cast were cited for obscenity. The theater manager panicked and canceled the rest of engagement. Harvard was undeterred and just moved it down the road to the Encore Theater, where it opened in April 1971. Harvard downplayed the hiccup, maintaining that the Basin Street Theater shows had just been rehearsals intended for a private audience.

Once again, Harvard granted interviews to the local newspapers, such as the San Francisco Chronicle, and once again he exaggerated the success of the play, saying that it had played for two months in Miami, seven weeks in Honolulu, and would transfer to Washington DC next. Now he boasted his own experience included “33 years of Hollywood and 122 major feature-length productions, eight television series, awards from the Vatican and the Edinburgh Festival, and a track record that included working with Universal, Paramount, and 20th Century Fox.” He claimed the reason he used a fake name ‘Emilio Portici’ was not because his stage play was pornographic, but rather because he was in the middle of “negotiating a major deal with MGM” and didn’t want to jeopardize it. All the bluster and boasting worked: the stage show was a hit again, and additional midnight performances were added to the twice-an-evening offering.

At the end of the San Francisco run, Harvard decided to retire the play: it had had a good run, but it was expensive to produce, flying and accommodating his actors and crew, and paying for potential legal fees to defend lawsuits. He decided to focus his efforts and money on his fledgling film studio. In mid-1971, he returned to Miami, and dedicated himself to his new activity: making sex films.

*

5. Rafael Remy and Emile Harvard – The Miami XXX Factory

So you may be wondering what this all has to do with Rafael Remy. After all, this is meant to be his story. When Harvard got back to South Florida, he called Rafael, now his go-to film man, and explained the plan – and he wanted Rafael to be his right-hand man.

His business model was simple: with the help of Leroy Griffith, Harvard would finance and produce sex features and shorts that he would send to labs up in New York for processing where they would then be distributed to theaters across the country. Harvard set up a studio at 1238 North Miami Avenue, and formed an inner circle of trusted associates that would deliver an inexpensive, rinse-and-repeat formula that would maximize profits. This small group consisted of Rafael, who would also be production manager, main cameraman, and editor; Jack Birch, a pockmark-faced wannabe actor who had aspirations to be a Jack Palance-style on-screen heavy, and Jack’s girlfriend Carol Kyzer, a quiet, blonde, part-time model who’d done topless layouts for Bunny Yeager; Brad Grinter, a veteran of the horror film scene in Florida who had just made Flesh Feast (1970), a terrible movie whose one claim to fame was its star, 1940s bombshell Veronica Lake; Brad’s son Randy, a 22-year-old who would be Rafael’s assistant; Harvard’s daughter, Esther, who was given the job of office manager; and finally there was Barry Bennett, the young actor who would take the lead performing role in the films.

Carol Kyzer, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Carol Kyzer, photographed by Bunny Yeager

Barry had an additional role – and a critically important one: he was the one who’d take the films to the labs in New York to get the film stock processed and the prints cut. It was a risky assignment: the U.S. Supreme Court still hadn’t come up with an agreed-upon definition of obscenity and so interstate transportation of pornography was a dicey proposition with offenders facing years of imprisonment. But Barry wanted the extra cash that Harvard promised him – so he figured he could deal with the dangers.

Due to the potential illegality of what they were all doing, most of the group took different names to mask their involvement: Harvard reverted to his ‘Emilio Portici’ identity, Rafael Remy became ‘Roberto Raphael’ – if he had a credit at all, Brad and Randy Grinter used any name – just as long as it wasn’t theirs, and most of the time it wasn’t, Jack Birch had a variety of Western-macho names like ‘Jack Colt’ or ‘Michael Powers’, Carol Kyzer became ‘Carol Connors’, a name that she would use for the next decade, and Barry Bennett took the name ‘Marc Brock.’ Harvard would be the nominal director of the films, but in practice, he would share the responsibility with Rafael.

For the next three years, Harvard’s studio churned out sex films on a regular basis: titles like Penny Wise (1970), The Good Fairy (1970), The Eighteen Carat Virgin (1971), Mary Jane (1972), Your Neighborhood Doc (1972), School Teachers Weekend Vacation (1972), and Female Stud Service (1972). Most of them were made according to a template loosely agreed with Leroy Griffith: each feature film would be roughly 65 minutes long, and would cost less than $15,000. Most were shot in Harvard’s small studio at 1238 North Miami Avenue, though they would occasionally venture out into fancy houses like a Coconut Grove mansion belonging to a friend of Harvard, Sepy Dobronyi.

Nearly all of them starred Barry Bennett, who, as ‘Marc Brock’, quickly became Florida’s leading male porno star. He wasn’t the most charismatic performer you’d ever seen but he could be relied upon to use his improv and comedy skills to fill the holes in the scripts. Many of the movies also featured Jack and Carol, who soon became a married couple.

All the films did ok but none were spectacular. Rafael worked hard behind the scenes, and nearly all of the crews consisted of his old Cuban friends, including José Prieto who came onboard for an occasional job. Randy Grinter remembers Rafael telling him that the softcore sex film business In Florida had been built by Cubans, and now it was Cubans who were responsible for the hard-core films too.

And then in 1972, Deep Throat became a national smash-hit: it had cost $25,000 and had made several millions for the New York mob that distributed it. It was essentially a New York film: the financing came from the Brooklyn-based Peraino family, and the director, stars, and crew were mostly New York-based. But Emile Harvard didn’t view it that way: ‘Deep Throat’ was shot in Miami, making ample use of the exteriors and locations that he normally used like Sepy Dobronyi’s pad, and two of his featured players, Jack and Carol, both had roles in it. For someone who had labored for the previous two years to make money in the business, Deep Throat’s wild success felt a kick in the teeth to Harvard. He was mad and resolved to get even. Crew members who worked with him remember him shouting, in his thick eastern European accent, about the fact that the success should have been his. Harvard reacted swiftly, increasing production, widening his distribution, and expanding his business: the least he could do was to cash in on the new bigger market that ‘Deep Throat’ had created.

*

6. XXX, after ‘Deep Throat’ (1973)

Emile Harvard and Leroy Griffith were strange bed-fellows, but their relationship was symbiotic and so they had regular contact about the sex film market – and how to exploit it. For example, Griffith suggested ripping off ‘Deep Throat’ by making a movie called Dear Throat (1973) saying that people would see the ads in the newspapers but not realize that they were two different films with similar names. Harvard obliged, making a cheap knockoff starring, who else?, Marc Brock and Carol Connors. It was blatant plagiarism, and so Harvard used a different name for the film – P. Arthur Murphy – fearing reprisals from the mob owners of ‘Deep Throat.’ It was one of an increasing number of different identities he started to use, as the legal heat increased around adult films. Thirty years after the war in which he’d hidden his identity to work undercover, Harvard still seemed incapable of living a simple life as himself.

Not that he’d grown afraid of publicity: Harvard gave a number of interviews to newspapers and magazines. In one of them, he used the name ‘Bruno’ – much to the amusement of the Cuban crews. One interview quoted ‘Bruno’ (“in a guttural European accent”) as someone who “used to be big in Hollywood” and that he was “only turning out this stuff between engagements.” The reporter was even invited to Harvard’s studio where he reported that all the technicians were Cuban, and that “Bruno’s studio contains, as scenery, an office desk, a couch, and a bed: the three essentials for a porno movie.” While he was there, Bruno warned him not to speak loudly as he was making a “quality movie” and the actors “are very sensitive about what they have to do.”

Harvard may have been unhappy about missing out on the ‘Deep Throat’ deep cash, but he was still doing pretty well – a fact that was evident to many of the Cuban crew, as one of them remembered: “Emile was a very different guy to us Cubans, but he liked us and always had work for us. He paid by the hour in cash at the end of each day, but we never hung out with him or anything like that. And we could all see that he was making big money.”

It was true: Harvard made no attempt to hide a pretty luxurious lifestyle – he lived on Palm Island, a man-made development, situated between the city of Miami and its glamorous suburb of Miami Beach. The area was famous for its celebrity residents, and neighbors had included gangsters Al Capone and Meyer Lansky, and the non-gangster, TV presenter Barbara Walters. Harvard drove to work every day from his large house in a new cherry-red Buick Centurion, and often talked about eating at Miami’s finest restaurants. It may have irritated some of the Cubans who worked for Harvard, but Rafael Remy was happy. As Harvard’s number two, he was faithful to a fault, despite the difference in the money they were earning. Rafael had become the glue who held everything together and he kept people happy. He ran a tight ship, making sure they had a right-sized team for every shoot, choosing actors and crew carefully, and making sure everyone was paid.

In 1973, Harvard confided in Rafael that he felt fatigued. Worse he’d started feeling pain in his joints and bones. He figured he was just getting old – he’d recently turned 60 – and said he wanted to take a step back and delegate more of the filmmaking to the others, like Rafael himself, Marc Brock, and Jack Birch.

When I spoke to Brock many years later, he remembered the change in how Harvard operated: “Emile was a control freak, and then all of a sudden, he handed the reins over to the rest of us, and so we started to alternate the directing duties.”

*

7. ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973) – and the (next) Cuban Rebellion

In October 1973, Harvard got Marc Brock to shoot his latest film, Daddy’s Rich. Marc was a reliable sex performer, having appeared in most of Harvard’s features and loops, but the Cubans on the crew knew he was a sloppy operator, being regularly picked up by the cops for petty misdemeanors like shoplifting, a small stash of weed, and minor DUIs. Marc put together a rough budget for the movie, but it was higher than normal. The film wasn’t materially different from the rest of Harvard’s efforts, but somehow Marc convinced a distracted Harvard that he needed more money this time.

For a start, there were ten crew members – more than double the normal number – and there was an inflated cast of nine. Then there was the location: Marc arranged with Sepy Dobronyi that they would shoot most it in the same Coconut Grove house where ‘Deep Throat’ had been shot the previous year. Rafael argued with Marc that there was no need for the exterior location, but Marc was adamant. And then Marc withheld payment from the Cuban crew after the first day. Harvard had always treated everyone fairly and so the crew were suspicious Marc promised that everyone would be paid the following day, but the Cubans were unconvinced, a clash erupted, and they nearly came to blows.

Sepy Dobronyi’s house, venue for the filming of ‘Deep Throat’ (1972)… and ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973)

Sepy Dobronyi’s house, venue for the filming of ‘Deep Throat’ (1972)… and ‘Daddy’s Rich’ (1973)

One of the crew that I spoke to years later remembered what happened next: “One of the guys, a grip on the shoot, took exception at Marc Brock after that – big time,” he said. “This grip was a new guy, and he was a hothead who liked to overreact. Next day, when the grip didn’t show, I called him up, and he just said, ‘Fuck Brock’. When I told him to do the right thing and come to the set, he threatened to call the cops and tell them about the shoot. We didn’t really believe him but we kept an eye out for the police that day.”

Sure enough, halfway through filming, Rafael noticed a cop car slowly coming up the road towards the house. He shouted in Spanish “Get the hell out of here now!”, and the crew scrambled their equipment together, much to the confusion of the semi-clad actors. Remarkably all eight crew on set that day made it out over the rear hedge, and down the lane, where they jumped into cars and fled the scene. They left Marc with Stan, his assistant director, as well as six actors, in the house – who were all arrested. Marc and Stan were charged with manufacturing obscene material, while the actors were charged with lewd and lascivious behavior, and indecent exposure. Sepy Dobronyi, the owner of the house, wasn’t helpful, making a statement to the newspapers that he was playing tennis at a nearby park at the time – and that the actors had broken into his home at which point his house guests had called the police.

Harvard, fearful of negative publicity for his business, called Leroy Griffith for help. Griffith snapped into action dispatching his main attorney, Alan Weinstein, to the precinct. Weinstein had been getting Griffith out of scrapes for years, including helping out when ‘Fear of Love’ had been shut down. Weinstein got everyone out of jail – and threw in an indignant statement to the press: “The police had no right to be on the premises,” he said. “There were more cops involved in arresting people taking pictures than there are on a murder case. Someone’s priorities are out of whack.”

The arrests caused a mini-media storm in the Miami newspapers, and for a few months, Harvard had to curb back his movie production schedule. Harvard blamed Marc Brock: he’d once viewed Brock as a protégé and an investment for the future, and so he’d ignored Marc’s legal indiscretions because he was essential in transporting the films up to the labs in New York, as well as being a reliable performer in front of the camera, but Harvard had had his fingers burned by this.

When Harvard looked into the finances of the film and saw that Marc had been using the inflated budget to line his own pockets, pilfering money for himself, he called Marc and told him he was fired.

*

8. Trouble in Wonderland

By 1974, it seemed that the immediate hardcore boom after ‘Deep Throat’ was starting to subside, and some of the players who’d been involved were looking to go legit – or at least, go more legit than being underground producers of hardcore smut.

Leroy Griffith still played Harvard’s XXX films in his theaters as a cash cow source of income, but he was branching out in other directions. For one thing, he decided to revive the burlesque variety shows that he’d pioneered in Miami in the 1960s, this time opening a big production, ‘Hello Burlesque’ in Miami Beach with strippers, comedians, and music acts.

Harvard was looking to diversify too. He’d acquired theaters of his own, including the Cameo at 1445 Washington Ave, and when he and Rafael Remy had to put their sex films on hiatus, they decided to make a different kind of film. Or as Harvard bellowed one day, “Let’s make a serious movie!”

Harvard’s daughter, Esther, had written a sensitive script called ‘Of Gentle Heart’ about an escaped convict who befriends a young boy. It was originally intended as a touching character study, but when Harvard got his hands on it, he couldn’t help himself. His exploitation instincts returned, and he renamed it Fugitive Killer (aka Fugitive Women) (1974). Rafael was on hand as always to oversee the production.

When the film was released, after a gentle opening on a wholesome and bucolic farm, it turned into a rape and murder exploitation film. Marketed with the catchphrase, “Once he started, he couldn’t stop! If he didn’t rape you, he killed you,” the film was a bizarre mess, and despite being distributed by Harry Novak’s Boxoffice International Pictures, Inc., it failed to raise much interest.

It turned out that the film’s lack of success was the least of Harvard’s concerns. They say that bad news comes in threes, and it was certainly true for Harvard in 1974. He’d already scaled back his sex film production as a result of the bust of ‘Daddy’s Rich’, when he lost his son, Roy, who died after a short illness. Then, Harvard received an explanation for the fatigue and pain he’d been experiencing: he was diagnosed with bone cancer. He began treatment immediately, and told Rafael they had to put all filmmaking on hold.